- What this Harvard and MIT alumnus started as online lessons within his family has now become the primary mode of instruction at teacher-strapped schools in southern India.

- Recently made available as an app on Samsung phones, and customizable in regional languages, his 3,000+ free lessons on all things under the sun have changed the way young children view homework.

- Patronized by Bill and Melinda Gates, his academy fetched him the distinction of being one of TIME magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world. According to Amazon, his book The One World Schoolhouse: Education Reimagined, published in October, is “destined to become one of the most influential books about education in our time.”

- Doubted by at least one critic of his TED talk who dubbed him a “rogue educator,” he is challenging the conventional teacher-student hierarchy in the classroom and making exams incidental to the learning experience.

- He owns one of the most coveted names in Indian popular culture and told us he would be happy to make a video some day with his celebrity namesake.

“The day before my physics final, one of my oldest friends committed suicide. I couldn’t focus, couldn’t think…Everything I learned vanished. I’m not sure who did your currents/resistors/etc tutorials but…Thank you. I had to relearn everything, and the way you put things made sense. Not to mention, and I don’t mean to sound odd, but your voice was really comforting.

I did very well on my final, and it got me through a rough night. I know it might not be your goal, helping people on that level…But seriously, thank you. – a fan”

We don’t know if Salman Khan has heard about the Bihar Coaching Institute (Control and Regulation) Act, but it may not be long before he starts getting angry mails from the captains of the eastern Indian state’s multi-crore coaching industry, already under stress from the Act’s dicta. For students from states such as Bihar, striving to break free from decades of underdevelopment, education is often the only tool for salvation. Every year, thousands of them vie for a few seats at the country’s premier institutions such as the IITs, creating a lucrative business case for ‘parallel education,’ aka coaching. Indifferent teachers and ramshackle infrastructure in the government schooling system has added to the lure of coaching classes, allegedly making it easy for them to get away with shoddy practices. To ensure fair play, the Bihar government passed the first-of- its-kind act in 2010, and it was promptly challenged by the state’s formidable coaching lobby in court for its rigid quality stipulations, which pose a serious threat to their business. In Salman Khan though, the lobbyists may have met a litigation-proof nemesis.

Salman Khan has all the right ingredients to be a superhit superfast in India, and rival our crorepati coaches. First of all, of course, he has that name! Secondly, he is no stranger to social contexts like Bihar’s, having successfully implanted his model of video-based learning in places such as Tanzania, Mongolia and Indonesia (not to mention his part-Indian roots). And thirdly, he does not so much coach as simply chat and coax, sans any trappings of sitting on judgment over his wards—many of whom he will never see in his life—or talking to them from Olympian heights, unlike many teachers in real-world classrooms.

That last point is critical to understanding Khan Academy’s incredible journey. What Khan started as a family favor—he volunteered to teach mathematics to his cousins through Yahoo! Doodle—has now caught the imagination of people like Bill Gates precisely because it offers everything that real-world classrooms don’t. It’s a long list, but here are some of Khan’s coolest carrots: you can pause and replay a lecture any time you want; you don’t have to worry about embarrassing yourself by repeatedly puzzling over the same concept; and you can make exams fit themselves into your life rather than the other way around. Sounds like the school we all wanted to go to, doesn’t it?!

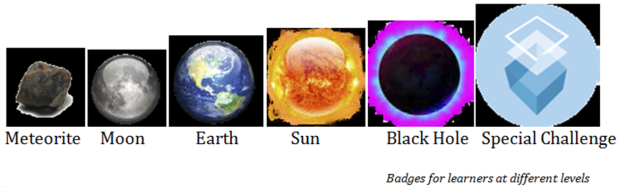

Khan Academy’s video lectures on all sorts of subjects, from complex calculus problems to the aesthetics of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup cans, are friendly to a fault, almost as if he is still only talking to his cousins. But underneath that gentle veneer lies an increasingly intuitive analytical mesh that gives the idea its real power—its software is now being prepared to intelligently predict what a learner should watch next, depending on their current skill level. Sal Khan shares this and other plans with us.

________________________________________________

“We have a simple belief: a student who understands, say, Algebra, well in India should be able to do great in Algebra in the US, or Russia or China or the UK, even though the official curricula would be very, very different. All our videos and exercises are built based on this belief. As regards reaching out to students with different proficiency levels—now that’s an interesting challenge.

Right from the beginning, I have been convinced about the ability of videos to help students pace themselves—the great thing about videos is that you can pause and play them whenever and however you like. Our software side, which is where most of our efforts are going in right now, is focused on customizing the learning experience even more, so that we can help students choose their lessons based on what their current skill levels are. We want to make sure that based on what you already know, you are able to make the best use of the half-hour or one hour you spend on our site.

The right fit

To achieve this level of customization, it is important that people who join our team understand the importance of design in pedagogy. However, what we want first and foremost from team members is authenticity. It is incredible how little authentic content is out there. I suspect that the reason for this is that every time someone is asked to run a big project, they put a group of people in a room, get them to write a script [on predefined terms] and get someone else to read it, and then unleash something that is very ‘polished’ but does not feel like it has been created by another human being. We too do lot of research and testing for our videos, but we make sure that they are conversational, intuitive, down to earth and not condescending. We also like humor in our videos—they don’t need to be comedy skits, but they should make people feel happy about watching them. We all have memories of sitting in a math class feeling very intimidated, very small, and the last thing we want is for our content to trigger those same associations.

Conversations that matter

The Khan Academy has become popular mainly through word of mouth spread by students and parents. However, far too often, we have seen that students and parents are only a part of the conversation on education—even though they are really who education is for. This needs to change. Conversations need to be centered on students and parents. The impact of such a change in a country like India would be particularly significant, given how important education is [for Indian families].

Even in the US, about 80% of our users are desi. They are a closely-knit community, very serious about education, very driven, very ambitious. If they discover a tool—or hear about one from their neighbors or neighbors’ children—that can help their kids learn better, they jump on it. I feel that parents everywhere in the world, of every culture and socioeconomic status, are like this. If they realize that there is a tool out there that is within their means and that can enhance the education and the future of their children, they will go for it. I think this is finally how new modes of education delivery should emerge and grow, driven by students and parents.

Slow and steady

With the cost of tablets and mobile devices becoming dramatically low, and with the content available becoming better and better every day, it is a valid concern that people may want to race ahead and try too many different things as fast as possible. Personally, I am a bit skeptical of any sweeping top-down initiatives. [I am not too aware of what is happening with the low-cost Aakash tablet in India which the government was planning to launch in educational institutions in order to promote video-based learning.] I would much rather try out something in one village and if it works—technically and in terms of the economics—spread it to a couple more, and then really scale it up over the next five-ten years. Otherwise, we could end up spending a lot of talent and resources—as well as a lot of political capital in some cases—to drive something that is still nascent and not ready to support huge numbers.

Back to school

It obviously is a great feeling that so many people all over the world are so excited about our academy and realize its potential. For a lot of people, [our model offers] a very useful tool, and we will of course continue to make it more and more useful. However, we are very careful about how we project ourselves. We never claim that we will replace traditional schools and colleges. We are clear that physical schools will continue to make up the core of what education should be. What we are trying to do is to hopefully be a tool that can make the experience of going to school more engaging, more interactive and more enjoyable, help peers talk to each other and learn from each other, and to generally make schools the kind of places that you and I wanted them to be. We are also quite happy being not-for-profit. We are too young, and being anything but not-for-profit would be rather shady. Sure, there are ways to generate revenue from what we do, but all of it will be ploughed right back into the organization.

There are a bunch of things that we would like to do as we grow bigger, but the most important thing would be to deepen our engagement with communities and help them to help each other. We would also like to get stronger on the analytics side, so that we understand our user better and make sure we give them content that continues to keep them interested. A huge task over the next eighteen months or so would be to fully localize our content, so that users can experience everything we have in Hindi, or Portuguese or Mandarin or whatever other language they like.

Finally—and I don’t know how seriously people take me when I say this—we would like to start our own schools. Of course, we are not going to start a million schools or compete with the existing ones. But now that the tool exists and the mindset exists to change how education has traditionally been conducted, we would like to create an institution that can demonstrate what can really be achieved.”

(As told to me for the Nov-Dec 2012 issue of The Smart Manager)